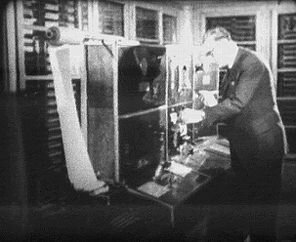

As Speiser [SPEI98] wrote about the operation of the Z4:

The machine was moved to ETH in September 1950, and, after a relatively short period, assumed operation. The Z4 proved to be reliable, and the frequency of breakdowns was well within the limits of what was compatible with satisfactory operation. Quite soon, the machine could be left running unattended overnight, which was quite unusual at this time. Zuse himself was understandable proud of this achievement. He was a man with a good sense of humor, and he once stated that the rattling of the relays of the Z4 was the only interesting thing in Zürichs nightlife. To appreciate the conditions under which we were working, I repeat that the machines power was 1000 operations per hour. For operational reasons, problems that lasted more than 100 hours could not be considered. Thus, 100 000 operations and 64 places of memory were the boundary conditions that were set. In the light of todays life where the term Gigaflops is an every-day word, and when memory is measured in gigabytes, it seems hard to grasp that useful work of any kind could be done with the Z4. And yet, at that time, at least on the European continent, there was no mathematical institute which had access to computing power comparable to ours.

Work with the Z4 was interactive in the true sense of the word. Of course, the term "interactive computing" did not exist at that time, for the simple reason that the situation when computing becomes non-interactive was never encountered. The mathematician was in the same time programmer and operator, and he could continually follow the running of his program. Intermediate results were printed out and could be inspected, the program could be modified if necessary. But the signals that the programmer received from the computer were not only optical, they were also acoustical. The clicking of the tape reader was an indication of how fast the program proceeded, or whether it had got stuck; and the rattling of the relays signaled what kind of operation was in process. This was a great help in spotting errors, both in hardware and in the programs.

In fact the memory, consisting of thousands of metal sheets, screws and pins, was the most reliable feature of the Z4. The Z4 worked very reliably and also worked during the night without supervision. Speiser, who was responsible for the maintenance of the Z4 also wrote [SPEI98]:

Although, as stated, reliability was quite good, I nevertheless remember many hours of searching for mistakes, which often had their roots in the malfunction of relay contacts due to dust. We also discovered several cold soldering joints that gradually failed to conduct; finding them was particularly bothersome, because they caused mistakes that were often intermittent. On two occasions I had to disassemble parts of the memory. This meant removing about 1000 pins and placing them back again. There were two kinds of pins, their lengths were 2.5 and 2.6 mm. If due to a mistake I mixed up one single pin, the entire memory was blocked, a very frustrating experience.

|