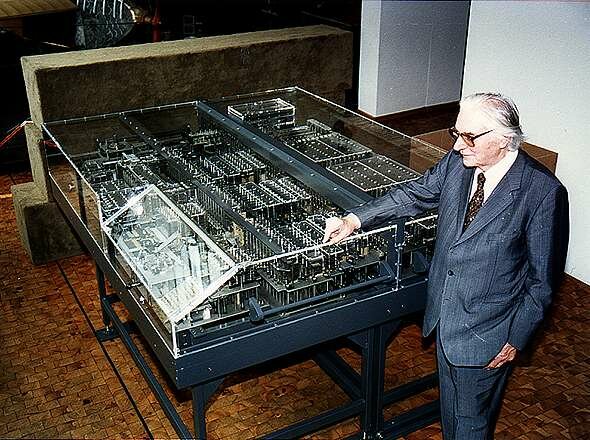

Fig.15. The punch tape (using 35mm standard movie film) and the punch tape reader of the Z1.

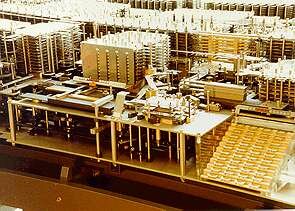

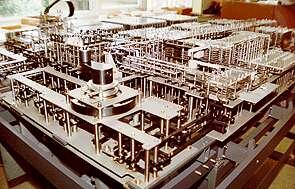

Fig.16. The full Z1.In the foreground is the manual crank for driving the clock frequency by hand.

The full Z1 is shown in Fig.16. In addition to the crank (in the foreground) for manually cycling the machine, there was also an electric motor, which was used to generate a clock frequency of one Hertz (one cycle per second). To the rear of this picture are the three blocks of memory, while the binary floating point arithmetic unit is on the right.