|

The Lu instruction at the beginning of the program instructs the input device to read a value for x. The Ld instruction at the end of the program directs the Z3 to display the result as a decimal number.

Minimal Design Principle and the Universal Computer (Turing)

Konrad Zuse followed a minimal design principle in the construction of his computers, because his goal was to build a powerful computing machine with minimal effort and cost. He really didn't have any other choice, because his parents were not rich and he didnt have much money. As far as he was concerned, the Z3 was the last in a series of trial machines (Z1-Z3) that were intended to pave the way to a machine that would be able to solve the mathematical problems of engineers and scientists.

Konrad Zuse was convinced that his computer could calculate all mathematical problems (in 1941 he told his friends that his machine was capable of playing chess), but he could not prove that this was he case. In fact it wasnt until 1998 (three years after Konrads death) that Raul Rojas [ROJA98a] formulated the proof that the Z3 was a truly universal computer in the sense of a Turing machine.

The S1 and S2 Computers

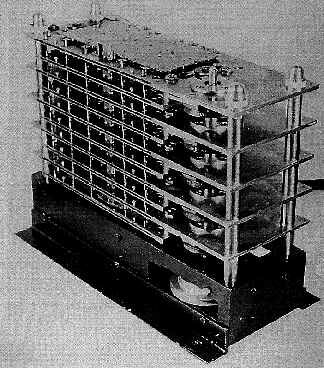

The S1 and S2 computers were mandated by the Henschel aircraft company in 1942/43. These were special developments for measuring the wings of airplanes. The S1 employed approximately 600 relays and had hardware-wired programs. The S2 was the successor of the S1, and consisted of approximately 800 relays and about 100 dial gages in order to measure the surface of the wings. It was used by the Henschel Aircraft Company since 1942. The S2 can be regarded as the first process computer in the world.

|